A new form of exploitation, known as “stakeholder capitalism,” is already being tested in many places around the world and prisons are among the main targets for its implementation, as they provide an ideal and literally captive market for its proof of concept.

by Raul Diego

Postmaster General Louis DeJoy is coming under fire again from Democratic lawmakers, as well as from the American Postal Workers Union, who are calling for President Joe Biden to pave the way for DeJoy’s removal after the Trump-appointee announced higher mailing fees and logistical changes that could further slow down mail. The US Postal Service (USPS) has already suffered a more than 50% drop in on-time arrivals for first-class mail deliveries, according to the service’s own data.

Nevertheless, thanks to the ubiquitous presence of high-speed internet, the personal communications of most Americans don’t seem to be fundamentally affected by the problems at USPS. Excluding the mail-in-ballots controversy leading up to the 2020 presidential election, the majority of the country remains little more than a curious spectator in what seems to be the inevitable demise of legacy long-distance message-carrying methods in the midst of a blossoming technological wonderland.

But, at least one key American demographic could well prove to be the canary in the coal mine in terms of the implications of a fully digitized mail system. The 2.3 million people currently incarcerated in America’s prison systems could be on the verge of altogether losing the privilege of receiving physical mail from friends and family if the Biden administration does nothing to stop the growing trend of handing over prison mail operations to companies like Smart Communications and its “Postal Mail Elimination” services.

A long-running problem

Promising to do away with the “longest running problems and security loopholes” of America’s prison mail systems, the privately-held corporation offers a ‘free’ service called MailGuard to state corrections facilities and county jails across the country.

MailGuard “filters” physical mail sent to inmates and delivers electronic versions to the prisoners via their proprietary SmartTablet or SmartKiosk platforms, according to Smart Communications’s website.

Among the most troubling issues surrounding such technologies is the risk they pose to prisoners’ Sixth Amendment right to carry on confidential communications with their legal counsel. In addition, the fees associated with the use of these services for inmates can constitute a violation of federal laws, which permit prisoners to send legal correspondence “regardless of their ability to pay for postage.”

Both DeJoy’s machinations at the USPS and the rise of private corporations offering to parse and deliver mail to prisoners via tablets and other costly hardware undermine the critical role physical mail plays in the life of the inmate population. And these developments also raise serious questions about corporate profiteering at the expense of American prisoners and taxpayers.

The Lawrence County, Indiana Sheriff’s Department recently closed a deal with one of the biggest players in this space, Securus Technologies, to furnish “JP6S tablets” to its 150 inmates. The tablets are being touted to the public as a way to offer “new communications and entertainment options, as well as free education and re-entry tools to help prepare [prisoners] for their release,” a service the jailed individuals can access through a “low-cost monthly” subscription.

Securus Technologies has been the target of civil rights activists like Bianca Tylek — founder of Worth Rises, a prisoner advocacy organization that seeks to dismantle “the prison industry” – who was “unimpressed” with Securus’s recent moves to address criticism over price-gouging and other exploitative practices against prisoners who are compelled to use their services to communicate with the outside world.

Acquired by a Beverly Hills private equity firm called Platinum Equities four years ago, the company has been known to charge up to $1 a minute for calls from prison, except in New York City where the cost was transferred to taxpayers.

Los Angeles billionaire and Detroit Pistons owner Tom Gores, who heads Platinum Equities, seems oddly sheepish about the relentless focus on his corporate assets by prison reform activists. Speaking on the controversy just a few weeks ago, Gores told The Detroit Free Press that although he would “get killed for saying this,” the prison communications industry should be the purview of nonprofits rather than of private interests.

The tech prison transition

That transition from for-profit to nonprofit seems to be exactly what is happening. A nonprofit backed by Twitter mogul Jack Dorsey, Google, and Schmidt Futures (Eric Schmidt’s philanthropic venture), among others, launched the Ameelio app less than a year ago to “disrupt the prison phone industry,” as it was described in a recent interview with the organization’s founder and Yale Law graduate, Uzoma “Zo” Orchingwa.

Ameelio is currently piloting with four states and plans to take over some of the services currently offered via predatory contract models, like those of Securus. Ameelio does not, however, solve the privacy problem nor does it completely eliminate the opportunities for financial exploitation of prisoners. In fact, it may simply open the door for far more sophisticated models, such as social impact bonds (SIB).

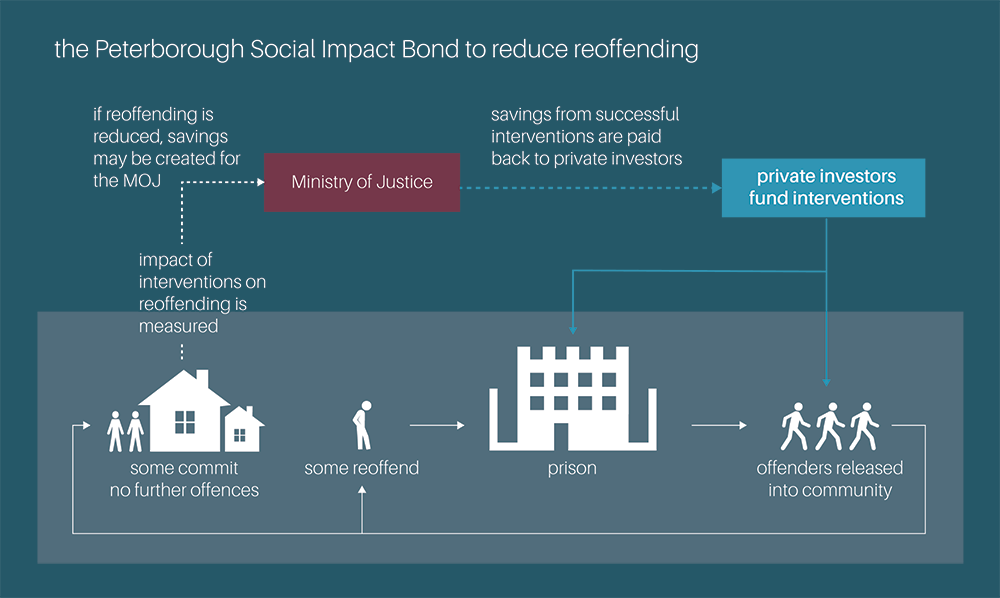

This graphic from a RAND Europe study shows how social impact bonds could be sold to private investors. Credit | Rand

The concept behind social impact bonds requires a fully digital ecosystem that can track and aggregate data on individuals who are a part of any kind of state or municipal service such as prisons. With such pervasive tracking, a subject’s progression through that system can be measured and linked to milestones tied to financial instruments, which investors (or stakeholders) can hold, buy or sell on the open market.

Known as stakeholder capitalism, this new form of exploitation is already being tested in many places around the world and prisons are among the main targets for its implementation, as they provide an ideal and literally captive market for its proof of concept.

Alison McDowell’s pioneering independent research on this topic has exposed many of the insidious ways in which pay-for-success schemes like SIBs and other human capital market ideas are being foisted onto America’s public education and healthcare systems through the “gamification” of schooling and health pathways.

Ameelio is set on gamifying inmates’ experience both inside the prison and in their outer-world interactions with “a variety of mental health-related content as well,… pre-designed content we developed ourselves, like crosswords, games and an article feature,” which, Orchingwa explains, allows relatives or friends to “include a link and we convert the news article into a letter that’s sent to their loved ones to keep them engaged with what’s going on in the world.”

Ameelio has also partnered with approximately 30 criminal justice organizations to facilitate communication with their clients, as well as a video conferencing platform called Northstar scheduled to launch in April 2021, which will practically complete the digital takeover of prison dynamics.

Feature photo | Anthony Plant reads from a tablet at his bunk at the New Hampshire State Prison for Men, in Concord, N.H. Charles Krupa | AP