In every one of the countries the United States has intervened in over the past decades, anti-democratic means are almost always used towards anti-democratic ends, all in the name of promoting democracy.

This week, the United States is convening a virtual “Summit for Democracy,” the first of its kind in what the State Department hopes to make an annual event.

“The summit will focus on challenges and opportunities facing democracies and will provide a platform for leaders to announce both individual and collective commitments, reforms, and initiatives to defend democracy and human rights at home and abroad,” the State Department says. Representatives from 110 governments have been invited.

Aiming to spark a “global democratic renewal” and “counter authoritarianism, combat corruption, and promote respect for human rights,” the summit’s billing includes all the usual buzzwords typically invoked by Washington to ratchet up pressure against its official enemies.

It’s no surprise that Washington has declined to invite its two biggest geopolitical foes, Russia and China. The two countries banded together to publish an opinion article in The National Interest, correctly characterizing the circus of a summit as a “product of [Washington’s] Cold-War mentality” aimed at stoking “ideological confrontation and a rift in the world.”

Anatoly Antonov and Qin Gang, the Russian and Chinese ambassadors to the U.S., jointly wrote:

Interfering in other countries’ internal affairs – under the pretext of fighting corruption, promoting democratic values, or protecting human rights – hindering their development, wielding the big stick of sanctions, and even infringing on their sovereignty, unity and territorial integrity go against the UN Charter and other basic norms of international law and are obviously anti-democratic.

That article, published on November 26, proved prescient. The United States, it turns out, has no intention of laying down its big stick. To mark the occasion of the summit, the U.S. Treasury Department revealed just days later that it would be imposing sanctions against those “who are engaged in malign activities that undermine democracy and democratic institutions around the world, including corruption, repression, organized crime, and serious human-rights abuse,” as a Treasury Department official told the Wall Street Journal.

It cannot be overstated how hypocritical it is that the United States is promoting its Summit for Democracy by taking actions that are illegal under international law. According to the United Nations Charter, Chapter VII, Article 41, only the United Nations Security Council may enact economic sanctions against United Nations members.

Nonetheless, Secretary-General of the United Nations Antonio Guterres will deliver opening remarks at the summit on Friday.

But this is just the beginning of provocations by the U.S. While opting to snub Russia and China from the summit, both Taiwan and Ukraine have been invited as a clear signal that the United States will leverage them to undermine its rivals, regardless of whether or not these confrontations are to the detriment of the people of Taiwan or Ukraine.

Spanning the globe, many other countries invited can hardly be classified as democratic: from apartheid Israel, where millions of Palestinians live as second-class citizens; to Brazil, whose leader Jair Bolsonaro this summer declared that “only God can oust me.”

Also invited is Venezuelan opposition activist Juan Guaido, who was declared by the United States to be the “interim president” of Venezuela. Nearly three years later, Guaido is still considered the “interim” leader of the country by the U.S. and its allies in the region – despite a failed attempt at a military coup, his coalition falling apart, and having never participated in a presidential election.

Guaido’s de facto Belarussian counterpart, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, an opposition figure who lost in the country’s 2020 presidential election, will also be speaking. Tsikhanouskaya may be favored to lead the country by around only four percent of Belarussians, but maintains a solid one hundred percent rate of support from Washington-based think tank fellows.

Other anti-democratic actors slated to speak include Nathan Law, a Chinese fugitive and former leading figure in the Hong Kong separatist movement, who has openly collaborated with the National Endowment for Democracy, a prominent tool in the U.S.’ destabilization arsenal and an offshoot of the CIA.

Those in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones

Rather than using its Summit for Democracy as a means of furthering its information warfare campaign against China and Russia, the American public would be better served if the government of the United States focused instead on cleaning up the mess in its own house.

Since the State Department has chosen to highlight the topic of democracy, it’s worth examining the state of democracy at home. Surprising no one, it’s not looking good.

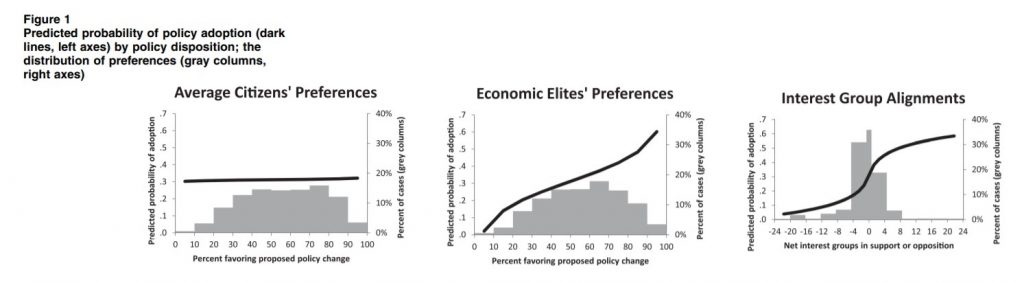

Take, for example, a peer-reviewed Princeton University study from 2014 entitled “Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens.” Professor of Public Policy Martin Gilens, alongside Professor of “Decision Making” Benjamin Page and a “small army of research assistants, gathered data on a large, diverse set of policy cases: 1,779 instances between 1981 and 2002 in which a national survey of the general public asked a favor/oppose question about a proposed policy change.”

“For each case, Gilens used the original survey data to assess responses by income level,” the study states.

What the researchers found may be shocking to many people around the world, but to U.S. citizens it is probably not all that surprising. “When one holds constant net interest-group alignments and the preferences of affluent Americans, it makes very little difference what the general public thinks,” the study found. “The probability of policy change is nearly the same (around 0.3) whether a tiny minority or a large majority of average citizens favor a proposed policy change.”

In layman’s terms, the policy preferences of average citizens have almost no bearing on the likelihood of a policy being adopted by the government. By contrast, the preferences of economic elites is highly correlated with the likelihood of a policy being adopted.

The study states:

The central point that emerges from our research is that economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while mass-based interest groups and average citizens have little or no independent influence.

There is a word for the kind of political system revealed by this study, and it is not “democracy,” nor is it flattering. That word is “oligarchy.”

Consider the results of this study in light of comments made by Chinese businessman Eric Li, who in 2017, years after the study’s release, commented that “in America you can change political parties, but you can’t change policies. In China, you cannot change the party, but you can change policies.”

While the United States has deemed China unworthy of being invited to its Summit for Democracy, these issues raise an important question: is the U.S. itself actually a democracy if its citizens get little to no say in governmental policy?

In assessing just how truly democratic the United States really is, there are other metrics to consider besides how much of a voice its citizens have.

In the United States, the people are supposedly represented in Congress, where the laws are made. So how are those guys doing? Well, as of October of this year, the most recent results available from Gallup, 75 percent of Americans disapprove of their performance. Considering figures from the past decade or so, these numbers are not all that shabby; congressional disapproval has peaked at 86 percent four times since 2011. Moreover, with partisan gerrymandering the norm and electoral districts looking more like Etch-A-Sketch drawings than cohesive or meaningful population groups, competitiveness in House of Representative races has dramatically declined in many districts, with just 43 of the seats up for grabs in 2020 being considered “competitive,” or about 10% of the House.’

Public perception of electoral integrity is also low: according to Harvard University’s Electoral Integrity Project, the U.S. ranks 57th out of 165 countries under this metric in elections between 2012 and 2018, and it’s worse in the U.S. than in “most liberal democracies in affluent post-industrial societies.”

“Structuctural problems undermining American democracy” include electoral laws and gerrymandering favoring incumbents (which may explain the consistently low approval ratings), a lack of transparency in campaign finance, and “communities of color experiencing difficulties in registering and voting.”

There are more metrics to consider, such as participation in the electoral process.

Because there is no official count of how many U.S. citizens in total are eligible to vote, the best figures we can get are from independent analysts. The most authoritative of them is Dr. Michael McDonald, professor of political science at the University of Florida who runs the United States Election Project. According to his research, 239.2 million people in the U.S. were eligible to vote in the 2020 presidential election. Yet according to the United States Election Project, only 66.2 percent of the “voting eligible public” voted in the presidential race, meaning that slightly more than a third of eligible voters stayed at home.

These dismal figures are despite the fact that “the percentage of nonvoters narrowed to the smallest proportion in 120 years,” according to a survey by the Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications, and National Public Radio.

With so little impact on policy and such disdain for the politicians running the show, it comes as no surprise that in the 2020 presidential election, 80.8 million eligible voters didn’t vote at all.

To put this in perspective, we can say that President Joe Biden managed to narrowly beat the couch in terms of the popular vote, but only by about 443,000 votes.

The aforementioned survey of 1,103 nonvoters found that while 29 percent said they didn’t vote because they were not registered, “the others cited reasons for abstaining such as a lack of interest in the election, the feeling that their vote wouldn’t make a difference or a general dislike for the candidates.”

Yet, despite President Biden’s triumphant victory over the couch, according to FiveThirtyEight, which aggregates polling data from various sources, his disapproval rating currently stands at 51.3 percent, with a measly 42.8 percent approving, worse than nearly every recent president at this stage in their term with the exception of Donald Trump.

Moving on from purely electoral democratic deficiencies, there’s also the major issue of economic injustice. According to United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights Philip Alston, following his visit to the United States in 2017, “more than one in every eight Americans were living in poverty.” That’s equal to 12.7 percent of the population, with “almost half” of them living in extreme poverty.

At the same time, child poverty rates are even higher, with 18 percent of children living in poverty. While most poor people are white, owing to the overall demographics of the United States, poverty rates by race reflect a racist dynamic, wherein 42 percent of Black children live in poverty.

“At the end of the day, particularly in a rich country like the USA, the persistence of extreme poverty is a political choice made by those in power. With political will, it could readily be eliminated,” Alston wrote.

Once again, it is worth comparing this reality to the recent developments in China, where the Communist Party this year announced the complete eradication of extreme poverty.

While many of the metrics considered here may seem basic, or obvious, they are worth raising in light of the United States’ decision to anoint itself an unelected arbiter of what countries are and what countries are not democracies.

Democracy Summit puts its worst foot forward

In an apparent attempt to make the entire affair even more absurd, the very first event at the Summit for Democracy speaks to what a sham the summit will be.

Entitled “Media Freedom and Sustainability,” the panel discussion featured opening remarks from U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and his Dutch and Canadian counterparts, Foreign Ministers Ben Knapen and Mélanie Joly.

The bitter irony of the United States hosting a panel on media freedom is not lost on many in the international community who have expressed alarm over the U.S. prosecution of WikiLeaks editor Julian Assange for the crime of journalism that has exposed the war crimes of the American empire.

A slap in the face to press freedom advocates, the panel focused on “how the international community can do more to protect journalists as well as how to reduce the vulnerability of independent media to closure or economic and political capture.”

Blinken cynically co-opted the language of racial justice in his opening remarks, decrying “journalism deserts” and rallying in defense of “at-risk journalists.”

Amnesty International’s secretary general, Agnes Callamard, moderated the panel.

As I noted on Twitter prior to the event, Amnesty International has called the U.S. prosecution of Assange “nothing short of a full-scale assault on the right to freedom of expression.” Callamard did not respond to my question whether she planned to raise Assange’s case during the event, despite my question being viewed on Twitter more than 25,000 times before it took place.

Amnesty’s Callamard likewise declined to bring up the case of Assange, as did all of the others involved with the panel.

Given the background of the panelists and other speakers associated with the press freedom event, it’s not surprising that Assange’s name was not dropped even once.

For example, Maria Ressa, winner of the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize and CEO of the news website Rappler, went from tweeting such headlines in 2010 as “If Assange is charged with espionage, what about news orgs?” to “Security reports reveal how Assange turned an embassy into a command post for election meddling” in 2019. Refusing to condemn Assange’s arrest, Ressa has also said that WikiLeaks’ publishing model “actually isn’t journalism.”

Ressa’s Rappler has been given $284,000 from the CIA cutout National Endowment for Democracy.

Also at the event: Bay Fang, the president of Radio Free Asia, an anti-Chinese propaganda outlet originally founded by the CIA; and Sana Safi, a journalist with the BBC – founded by the British government.

Bay Fang opted to ignore the true history of the organization she leads, telling the audience that it was “created by Congress.”

Another little-known panelist is Jennifer Avila Reyes, editor-in-chief of the Honduran news outlet ContraCorriente, which has received about $75,000 from the National Endowment for Democracy. During the panel, she called her outlet’s business model “revolutionary.”

These are the voices selected by the State Department to tell the world the burning answer to the question “How can we strengthen efforts to ensure independent media can safely report around the world?”

You can’t make this stuff up.

The most feared phrase in the world

Perhaps the scariest part of the U.S.-hosted Summit for Democracy is none other than the U.S.’ legacy in terms of “democracy promotion,” which is, more often than not, conducted at the barrel of a gun.

This legacy was perfectly characterized by the spokesman for China’s foreign ministry, Lijian Zhao, who tweeted a meme simply showing before-and-after photos of foreign cities since the U.S. sought to impose democracy on other countries.

Whether it be Syria, Libya, Iraq, Afghanistan, Hong Kong, Tibet, Belarus, Ukraine, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Honduras or any of the countries the United States has intervened in over the past decades, anti-democratic means are almost always used towards anti-democratic ends, all in the name of promoting democracy.

Libya is a good example, as the chief advocate for “humanitarian intervention” in that country, Samantha Power, is getting two speaking slots during the Summit for Democracy.

Back in 2011, the United States and NATO-backed anti-government jihadists with weapons and air support, allowing them to publicly lynch Libya’s leader, Muammar Gaddafi. What ensued was Libya’s decline from being the most prosperous nation in Africa to having open-air slave markets.

Ten years later, the humanitarian situation there is devastating, but there is finally some hope on the horizon, as the country will hold a presidential election later this month. It’s worth noting that the two frontrunners in the election are widely considered to be Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, the son of Muammar Gaddafi, and warlord Khalifa Haftar, a former CIA asset.

When the majority of the world hears that the United States is seeking to “promote democracy,” it is this style of regime-change operation that is immediately called to mind.

Let’s all hope the Summit for Democracy has more bark than bite.

Feature photo | President Joe Biden listens as he meets virtually with Chinese President Xi Jinping from the Roosevelt Room of the White House in Washington, Nov. 15, 2021. Susan Walsh | AP

True. The US should not even have come up with this ridiculous idea, but more importantly, the US is not a democracy, it’s a constitutional republic.