Three years on from the explosive Julian Assange/Paul Manafort story, we question whether the Guardian has honored its stated commitment to the truth.

MANCHESTER, ENGLAND — In 1921, the Manchester Guardian’s editor, Charles Prestwich Scott, marked the newspaper’s centenary with an essay entitled “A Hundred Years.” In it, Scott declared that a newspaper’s “primary office is the gathering of news. …Comment is free, but facts are sacred.”

One hundred years on from Scott’s famous essay, and on the three-year anniversary of the Guardian’s Julian Assange/Paul Manafort story, we question whether the Guardian’s coverage of Julian Assange has honored the newspaper’s stated commitment to the truth.

Based on private communications between a Guardian correspondent and their source inside a security company at the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, as well as two exclusive interviews, we trace the events behind two of the Guardian’s most explosive stories this decade.

“Russia’s secret plan to help Julian Assange escape from UK”

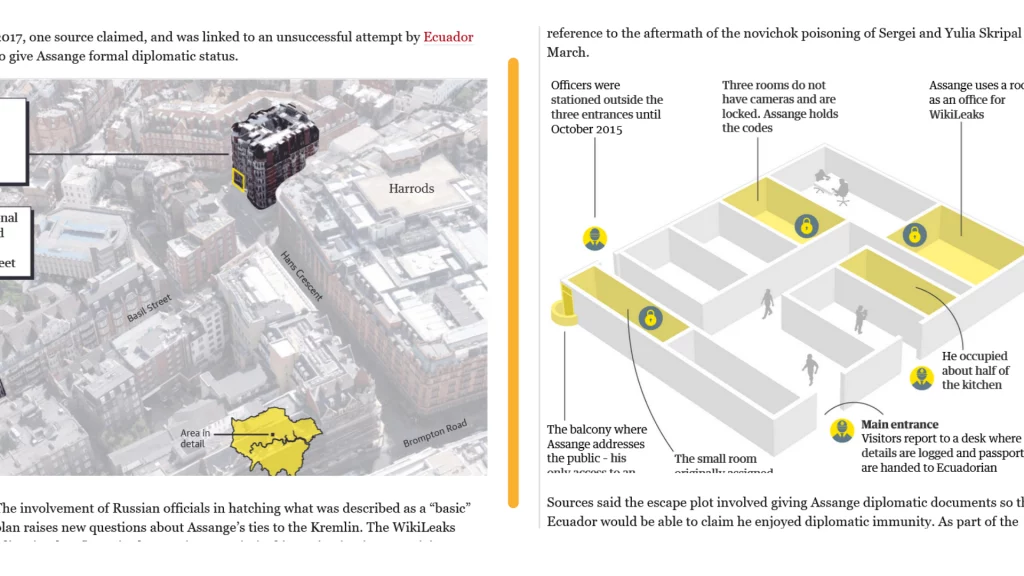

On September 21, 2018, the Guardian published a bombshell report entitled “Revealed: Russia’s secret plan to help Julian Assange escape from UK.” The story detailed an alleged conspiracy between Russian diplomats and WikiLeaks to illicitly smuggle Assange out of the Ecuadorian Embassy in London.

During the months before publication, Guardian correspondent Stephanie Kirchgaessner seemed eager to connect Assange to a Russian plot to escape the embassy.

On July 12, 2018, Kirchgaessner wrote to a source at UC Global, the private security company hired by the Ecuadorian government to protect Assange and its embassy in London: “We heard that the Russians wanted to help Assange and maybe get him a diplomatic visa. This was last year. But then the plan was rejected. By the Russians or by Assange? Why? Can you help? Do you know?”

On August 30, 2018, three weeks before publication, Kirchgaessner wrote again: “Hello. I am trying you again. I want to write a story about the discussions last year to get JA out of the embassy. The talks that happened with the Russians. Can I send you some questions?”

When the article was eventually published, the authors — Kirchgaessner, Dan Collyns, and Luke Harding — claimed that “Russian diplomats held secret talks in London … with people close to Julian Assange to assess whether they could help him flee the UK” in late 2017.

Though it was acknowledged that “details of the Assange escape plan are sketchy,” the authors used two unnamed sources to assert that Fidel Narváez, the former consul at the Ecuadorian Embassy, “served as a point of contact with Moscow.”

The story appeared to add weight to the “Russiagate” narrative – the belief that the Donald Trump campaign colluded with Russia to subvert the 2016 U.S. presidential election, with help from WikiLeaks. The authors noted that the alleged escape plan “raises new questions about Assange’s ties to the Kremlin.”

Two individuals with first-hand knowledge of events reject the Guardian’s story, however, and provide details about what really happened in late 2017 when Assange tried to leave the embassy.

In an exclusive interview, Aitor Martinez, a lawyer who oversaw Ecuador’s effort to grant Assange diplomatic protection, explained that plans were drawn up to appoint Assange as an Ecuadorian diplomat and transport him to a third country. That way, Assange could legally leave the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, where he was subject to arbitrary detention and where his health was declining.

Martinez drew up a list of countries that Ecuador should approach: China, Serbia, Greece, Bolivia, Venezuela or Cuba, noting:

Of course, they were the countries that don’t have good relations with the U.S. and could accept the appointment. Russia was never, ever on that list. There was a huge conspiracy theory in the U.S. with Russiagate; it didn’t make sense. So those were the countries.”

Martinez continued:

It took two or three weeks and we didn’t get any answer from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. And suddenly the Ministry said that they had appointed him to Russia.”

Foreign Minister María Fernanda Espinosa’s cousin worked at the Ecuadorian Embassy in Moscow and, through this cousin, she concocted a plan to appoint Assange to the one country that was the subject of mass-media hysteria.

“Julian and all of us at the legal team refused this appointment,” Martinez explained. “We said, ‘that’s crazy, what are you talking about?’ We refused.”

After Assange’s legal team refused, a second passport was issued to replace the diplomatic passport appointed to Russia, and Martinez personally brought the second passport to Assange at the embassy.

On December 21, Rommy Vallejo — the head of the Ecuadorian intelligence agency, Senain — visited Assange at the embassy to discuss the logistics for his transfer to a third country. Martinez said:

As soon as Vallejo arrived, he left his mobile phone at the entrance. And UC Global opened the mobile and took the IMEI code and also the sim card, as usual. Take into account that Senain was the entity that hired UC Global and this was the chief of Senain, and they spied on him.”

Martinez continued, referring to open court documents:

According to the UC Global chat, they were listening through the door and everything. They knew everything about the operation and we didn’t know they were spying on us, and reporting everything to the Americans, according to the witness declarations before the Spanish court.”

Martinez can reveal how, over the following days, the U.S. learned of Assange’s plans to leave the embassy. The Minister of Foreign Affairs called Martinez and asked:

What the hell happened? This is crazy, this operation plan was secret, was handled just by five or six people, and suddenly the U.S. ambassador in Quito came to my office and told me: ‘We know that Julian Assange is about to leave the embassy using a diplomatic passport, and we will never allow it.’”

Martinez explained that, at the time, Assange’s legal team couldn’t figure out how the Americans learned about this operation. “Now we can assume that it was because UC Global sent information about the plan. So, she [the foreign minister] said we have to stop everything because the Americans know,” he said.

At this time, the U.S. intelligence agencies were pressuring UC Global to link Assange with Russia. Martinez said:

UC Global drafted exaggerated and faked reports for the Americans. The protected [UC Global] witness claimed before a court that they had drafted exaggerated reports just to feed the Americans with information and to show that UC Global is very important for them at the embassy. If you check UC Global reports, it’s very funny; they make up everything.”

A recent Yahoo! News article suggests that these reports were taken seriously.

As well as listening through the wall, UC Global staff secretly recorded video and audio footage of Assange and Vallejo’s meeting. “They even created a Dropbox link to send it – they took the data, cut the conversation and sent it to Morales,” said Martinez. This footage was then presumably sent to Morales’s handlers in the U.S.

On November 12, 2018, Kirchgaessner contacted a source within UC Global requesting access to the transcript of Assange’s meeting with Vallejo.

Kirchgaessner wrote: “Hola. The transcript?”

Her source responded: “In this moment its [sic] difficult I think tomorrow I can”

Kirchgaessner was thankful: “Really? That would be amazing. You know which one I mean?” The next day, Kirchgaessner messaged again: “Hello. I mean the one with Rommy Vallejo.”

Kirchgaessner never received the transcript. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that the Guardian knew that a security company hired to protect Assange was in fact compiling transcripts on his private meetings long before this became public knowledge, and this wasn’t treated as the story. The Guardian instead promoted a narrative that Assange’s team was conspiring with Russia to illicitly flee the embassy.

To the contrary, Martinez emphasised that Ecuador had tried to help Assange leave the embassy through legal diplomatic channels, before the U.S. caught wind of the plan through a corrupt security firm that was clandestinely spying on Assange.

“A lot of mistakes”

Fidel Narváez, former consul at the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, categorically denies holding secret discussions with Russian diplomats. Narváez said:

I challenged the Guardian and I said this is false information – there was no Russian escape plan. To start with there was not an escape plan – escape, which means something clandestine, illicit, something not legal. That, there was not ever. Let alone something devised or orchestrated by a third country.”

Narváez lodged a formal complaint against the Guardian, attesting that “the Guardian has not, and cannot, substantiate with solid evidence its […] false assertions” that “Russian diplomats held secret talks in London last year;” and that “a tentative plan was devised that would have seen the WikiLeaks founder smuggled out of Ecuador’s London Embassy.”

On advice from its internal regulator, the Guardian amended the article to emphasize that “the plan in relation to Mr. Assange’s ability to be able to leave the Ecuadorian Embassy was not devised or instigated by Russia,” and that “there was nothing illicit about the ‘plan’ as described in the Article.”

Guardian admits its reporters L. Harding, S. Kirchgaessner, and D. Collyns gave a “misleading impression to readers” and breached paper’s code in one of infamous series of fake news stories about Assange from 2018 which helped put him in Belmarsh.

There will be no repercussions. pic.twitter.com/VbDE2WNPlX

— Matt Kennard (@kennardmatt) December 23, 2019

The Guardian’s climbdown from its original assertions suggests a loss of confidence in the information provided by its unnamed sources. Indeed, Kirchgaessner was warned by a source inside UC Global that the Guardian was being fed with false information from questionable sources months before the article was published.

On May 16, 2018, following the Guardian’s reporting on Operation Hotel (Ecuador’s multi-million-dollar operation to support Assange’s embassy stay), Kirchgaessner was told by a UC Global source:

I’ve read part of your article and [Ecuadorian news agency] plan V; there are a lot of mistakes and things that are confused or mixed; there are people who have provided that information so you do not know why they have given that …”

Perhaps more concerningly, Kirchgaessner appeared to know about the relationship between UC Global’s activities at the Ecuadorian Embassy in London and the security company’s proximity to Trump megadonor Sheldon Adelson almost a year before it became public knowledge.

UC Global’s loyalties had shifted in 2016, when its CEO David Morales attended a security fair in Las Vegas and won a contract to guard Queen Miri, a multi-million-dollar yacht owned by Adelson. “Given that Adelson already had a substantial security team assigned to guard him and his family at all times,” wrote Max Blumenthal, “the contract between UC Global and Adelson’s Las Vegas Sands was clearly the cover for a devious espionage campaign apparently overseen by the CIA.” Blumenthal continued:

Throughout the black operations campaign, U.S. intelligence appears to have worked through Adelson’s Las Vegas Sands, a company that had previously served as an alleged front for a CIA blackmail operation several years earlier. The operations formally began once Adelson’s hand-picked presidential candidate, Donald Trump, entered the White House in January 2017.

The relationship between Adelson and UC Global’s operations at the Ecuadorian Embassy was first reported in El País in September 2019. Yet on October 12, 2018, Kirchgaessner emailed her source within UC Global: “Also the [Las Vegas] Sands and Sheldon Adelson – did he pay for the embassy to move?”

If Kirchgaessner knew about the relationship between Adelson and UC Global’s activities at the Ecuadorian Embassy, why was it not reported at the time? Indeed, evidence of an elaborate spying operation on Assange, with links to the Republican Party and the Trump administration, would seem to disrupt the narrative of a secret Assange-Trump-Russia plot to subvert American politics – a narrative that the Guardian would not abandon easily.

“Manafort held secret talks with Assange in Ecuadorian Embassy”

On November 27, 2018, while Narváez’s formal complaint to the Guardian about its Assange coverage was still being processed, the newspaper published another blockbuster story claiming that Paul Manafort, Donald Trump’s campaign manager and key aide during the 2016 U.S. presidential election, had “held secret talks with Julian Assange inside the Ecuadorian Embassy in London” in 2013, 2015, and Spring 2016.

The story was immediately picked up by the world’s largest news outlets, including CNN, MSNBC, the Daily Mail, and the Los Angeles Times. “If it’s right,” commented a U.S. national security reporter, “it might be the biggest get this year.”

Indeed, the article appeared to provide additional evidence of “collusion” between WikiLeaks, Trump, and Russia in the lead-up to the 2016 U.S. election, during which time WikiLeaks released thousands of Democratic National Committee emails.

As the article’s authors, Luke Harding and Dan Collyns, claimed, the last alleged meeting between Assange and Manafort in Spring 2016 “is likely to come under scrutiny and could interest Robert Mueller, the special prosecutor who is investigating alleged collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia.”

The Guardian’s Manafort scoop began to unravel almost as soon as it was published.

Remember this day when the Guardian permitted a serial fabricator to totally destroy the paper’s reputation. @WikiLeaks is willing to bet the Guardian a million dollars and its editor’s head that Manafort never met Assange. https://t.co/R2Qn6rLQjn

— WikiLeaks (@wikileaks) November 27, 2018

The WikiLeaks Twitter account responded: “Remember this day when the Guardian permitted a serial fabricator to totally destroy the paper’s reputation. @WikiLeaks is willing to bet the Guardian a million dollars and its editor’s head that Manafort never met Assange.” Both Manafort and Assange denied that any of the visits took place.

Indeed, even the Guardian didn’t seem sure.

Though the Guardian’s sources were able to offer precise details about Manafort’s appearance (“casually dressed when he exited the embassy, wearing sandy-coloured chinos, a cardigan and a light-coloured shirt”) as well as the meeting’s duration (it “lasted about 40 minutes”), the authors were unable to establish exactly when Manafort allegedly visited.

Within a request for comment sent to WikiLeaks shortly before the article was published, Harding was not even able to specify during which month Manafort’s 2016 visit supposedly occurred. The meeting “took place,” Harding wrote, “in or around March 2016, around the time Manafort joined Donald Trump’s presidential campaign,” a detail that remained vague within the published article.

In the time since, the Guardian appears to have lost even more confidence in its own report.

Within hours of publication, the Guardian modified its headline to add “sources say” to the original claim that “Manafort held secret talks with Assange in Ecuadorian embassy.” The print edition, issued one day after online publication, added inverted commas: “Manafort ‘held secret talks with Assange’.”

Ninety minutes after publication the Guardian modifies its “Manafort held secret talks with Assange” headline to add “, sources say”. pic.twitter.com/zcg8cQcYGq

— WikiLeaks (@wikileaks) November 27, 2018

The main body of the report was also modified. Whereas the original claimed that “It is unclear why Manafort wanted to see Assange and what was discussed,” an updated version read that “It is unclear why Manafort would have wanted to see Assange and what was discussed.” [emphasis added]

Harding’s 2020 book, Shadow State: Murder, Mayhem, and Russia’s Remaking of the West, moreover, makes no mention of Manafort’s alleged meetings with Assange, even though the subject matter’s clear focus is malign Russian involvement in Western politics. Mueller did not mention the alleged meeting in his report on Russian interference in the 2016 election.

Despite watering down the article’s key claims, the Guardian has yet to add any correction notes or provide a retraction.

Visitor’s log

In paragraph 14 of the Guardian’s Manafort story, the authors note that: “Visitors normally register with embassy security guards and show their passports. Sources in Ecuador, however, say Manafort was not logged.”

It is curious that the Guardian glided over this crucial point. Narváez, who was in charge of the day-to-day functioning of the embassy, asserted that nobody could enter the building without being logged. Visitors required written approval from the ambassador, before registering their visit with security personnel and leaving a copy of their identification, which would be added to the visitor’s log.

Private UC Global discussions raise even more questions.

On November 22, 2018, five days before the Guardian published its Manafort story, an email was sent from UC Global CEO David Morales, asking: “Do we have a record that Paul Manafort during 2013, 2015, and 2016 visited the embassy?” UC Global staff discussed the matter:

Staff A: Hello… send me the name to search for

Staff B: Paul Manafort

Staff A: Ok, I’ll look and let you know

Any date?

I can’t find anything

Staff B: So there’s nothing?

Staff A: I can only find two Pauls… Stafford and Nigel

It seems that the Guardian’s request for information on visits to the embassy was flushed through Ecuadorian intelligence to UC Global and came back negative. Why did the Guardian glide over crucial evidence that contradicted its key claim, without offering any attempt at explaining why Manafort was not in the visitor’s log?

Indeed, the Guardian had relied on the visitor’s log for a separate story, and had privileged access to it.

On May 6, 2018, Kirchgaessner contacted a source within UC Global, saying:

I am interested in Nigel Farage because he went to see [Assange] once in 2017 and said it was the only time he went to see him. But other people think he went more and I am interested in knowing if that is true. Farage pushed for Brexit and he was also close to the Trump campaign.”

On May 18, 2018, Kirchgaessner emailed once more: “Have you seen what we published this week in the Guardian? We didn’t include the name of the company [UC Global]. […] Could you send me the list of visitors for the first week [sic] of 2016 (January – June 2016)?”

It is also curious that no video or photo evidence of Manafort’s alleged visit was provided, especially given that the Guardian had lines to access the embassy’s CCTV records.

On May 14, 2018, Kirchgaessner emailed a source at UC Global, asking: “Can you bring the video again of him [Assange] outside when you come [to a meeting] tomorrow?” Four days later, Kirchgaessner emailed again: “We are very interested in the video of JA [Julian Assange] outside. Do you think that you could get the film in a few weeks?”

If the Guardian could access CCTV footage at the embassy, why was it not able to provide material evidence of Manafort’s alleged visit? Did the Guardian even ask?

Concealed author

To this day, the online version of the Guardian’s Manafort story presents only two authors: Luke Harding and Dan Collyns.

In early December 2018, however, WikiLeaks wrote that the Guardian had “mysteriously hid[den the] third author of fabricated front page story” – Ecuadorian political activist and journalist Fernando Villavicencio.

In 2014, the Ecuadorian government pointed the finger at Villavicencio for providing the Guardian with allegedly forged documents relating to a secret $1billion “deal with a Chinese bank to drill for oil under the Yasuni national park in the Amazon.”

Even before the Guardian’s Manafort story was published, Villavicencio had promoted doubtful claims about Assange’s visitors at the Ecuadorian Embassy. On May 16, 2018, Villavicencio and Cristina Solórzano correctly wrote in La Fuente that “[Nigel] Farage visited Assange in March of last year, stayed for roughly 40 minutes and when asked about why he visited, responded ‘I don’t remember’.”

However, they added that, according to their source, “Farage returned to the embassy the next month, entering 28 April 2018 at 17:10 and leaving at 19:40.”

The allegation was almost certainly false. In late March 2018, the Ecuadorian authorities had removed Assange’s access to the outside world, including a ban on visitors. These rights were only partially restored in October 2018, meaning Farage had supposedly visited while Assange could not accept visitors.

Questions

A number of crucial questions remain unanswered by the Guardian:

- What did Kirchgaessner know about the relationship between UC Global, Sheldon Adelson, and the Ecuadorian Embassy security operation in 2018, before this was public knowledge? Why was this not reported on at the time?

- Why did the Guardian not report on the fact that Assange’s private conversations were being transcribed by a security company that was supposed to be protecting him?

- Did the Guardian continue to use sources in Ecuador’s intelligence service after it was warned that they were spreading disinformation?

- Given that the Guardian had lines to access CCTV footage at the Ecuadorian Embassy, did it try to attain material evidence of Manafort’s alleged visit? If not, why?

- Why has the Guardian not added any correction notes or provided a retraction to its Manafort story?

- Why is the third author of the Manafort story, Fernando Villavicencio, still not listed on the Guardian’s website? Why was he seen as a reputable journalist to cover Assange?

Until these questions are answered, the newspaper cannot credibly defend itself against the charge that it has committed serious journalistic malpractice in its coverage of Julian Assange.

The Guardian did not respond to a request for comment at the time of publication.

Feature photo | A poster of Julian Assange is seen inside a handbag of a protestor as supporters stage a demonstration outside the High Court in London, Oct. 27, 2021. Frank Augstein | AP