To what extent is the ongoing conflict between Israel and the Gaza Strip intertwined with the region’s oil and gas resources? Since the year 2000, upon the discovery of gas fields in Gaza, the Israeli government has obstructed the Palestinian people and their representatives from harnessing the advantages of their natural resources. Let’s look at the facts.

The awareness and potential of Gaza’s gas fields have been prevalent since their initial discovery in 2000. Former Palestinian Authority President Yasser Arafat esteemed them as a divine gift. Nevertheless, Gaza has remained unable to profit from its natural gas fields, notably identified as the Gaza Marine.

In recent years, discussions have persisted among Israeli stakeholders, Egyptian firms, and the Palestinian Authority regarding the utilization of gas resources off the coast of the Gaza Strip and the method of tapping into this substantial wealth. However, somewhat obscured from public knowledge is the reality that during Israel’s initiation of conflict with Gaza in 2008, extending into 2009, Israel exploited that period to essentially seize control of the Gaza Marine, preventing its development by the Palestinian people. This occurred despite the fact that it fell under the jurisdiction of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) as stipulated in the Oslo Accords, thereby securing its status as an exclusive Palestinian economic zone.

In recent historical context, Hezbollah, the armed faction safeguarding Lebanese territory, resorted to threatening war with Israel and targeting its gas fields unless Israel ceded rights to the segments of these fields situated in Lebanese territorial waters to the Lebanese government. Succumbing to Hezbollah’s pressure, the Israeli government reluctantly relented and signed an agreement permitting the Lebanese populace to exploit their natural resources peacefully. Notably, throughout this crisis, the rights of Gazans over their gas fields were never disputed.

Following Hezbollah and Lebanon’s success in reclaiming sovereignty over their natural resources, Hamas initiated a similar endeavor. It issued a warning to Israel, asserting retaliation if Israel attempted to appropriate Gaza’s resources. Subsequently, substantial negotiations between the Palestinian Authority, Egypt, and Hamas ensued, culminating in Hamas’s consent last June to allow the development of the Gaza Marine contingent upon receiving a share of the gas field revenue.

After the October 7 Hamas attack, Israel found itself compelled to close down its primary gas field, the Tamar Field, which constitutes the majority of its gas production. Grappling with the economic ramifications of this closure, Israel opted to issue new licenses to diverse energy companies to fortify its position and reassure oil companies about the economic potential of developing Israeli gas.

Since 2000, Israel has obstructed the Palestinian people from benefiting from their gas fields, which, by international law and the agreements endorsed by Israel, rightfully belong to the Palestinian population. Presently, the sole impediment for Israel is Hamas. Eliminating Hamas would ostensibly enable Israel to exert unchallenged control over Gaza’s gas resources.

BILLION DOLLAR ISRAELI GAS GRAB BEHIND PAST 15 YEARS OF WAR ON GAZA

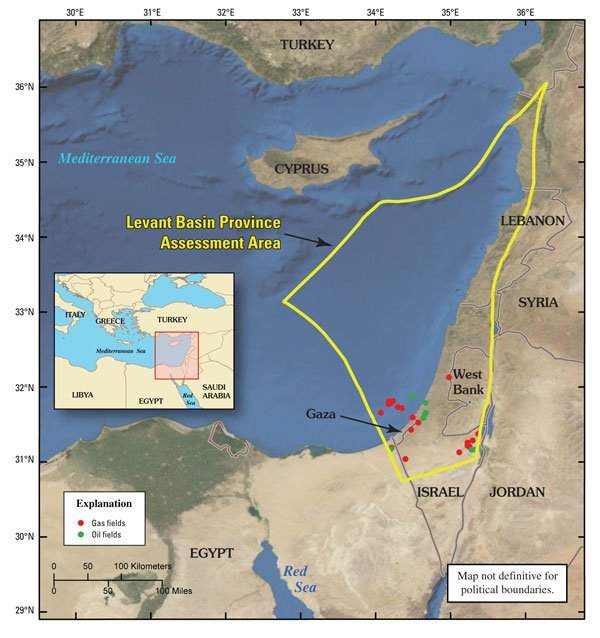

Energy consumption in the Mediterranean is estimated to increase by up to 50 percent over the next 25 years. The heightened demand comes at a time when gas in the Levant Basin, estimated to contain 1.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil and an average of 122 trillion cubic feet of gas, is being divvied up among nations with territorial claims to the waters, including Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, Egypt, Cyprus, and Turkey.

With these claims, of course, comes potential for conflict.

Michael Schwartz, Distinguished Teaching Professor in the Department of Sociology at Stony Brook University in New York and author of “War Without End: The Iraq War in Context,” told MintPress News that conflict for these resources has already begun.

In fact, he explained, energy resources are the root cause of every conflict the Israelis have had with the Palestinians for at least the last 15 years.

Schwartz argues that natural gas located off the coast of the Gaza Strip in Palestinian waters is at the heart of the last five major Israeli military actions against Palestine: Former Israeli Prime Minister and Defense Minister Ehud Barak’s orders for the Israeli navy to control Gaza’s coastal waters in the early 2000s; Then-Prime Minister Ehud Olmert’s blockade of the Gaza Strip on June 15, 2007; Operation Cast Lead in 2008; Operation Returning Echo in 2012; and Operation Protective Edge, which took place last summer.

Schwartz says an impending gas deal with Russia’s Gazprom, the world’s largest extractor of natural gas, was the precipitating factor behind Israel’s attack on the Gaza Strip last summer, which led to the deaths of over 2,300 people and the displacement of another 500,000.

Schwartz explained:

At the beginning of 2014, they [the Palestinians] had come to a preliminary agreement with Gazprom brokered by the Putin government with implicit promises that the Russian navy would protect their [Palestinian] facilities, and very explicitly saying, ‘We’re going to cut Israel out of it altogether.’”

The exploration agreement between the two entities was signed in 2013, at about the same time Russia had made another agreement with Syria and Lebanon, he said.

In a forthcoming article authored by Schwartz and forwarded to MintPress, he writes:

With the Gazprom Gaza development set to begin in 2014 and thus consolidate the Russian presence in the Levantine Basin, the Israelis once again sought a military solution. After a year of planning, Operation Protective Edge was launched in June, with two hydrocarbon-related goals: demonstrating to the Russians that Israel would be able and willing to prevent activation of the Gazprom contract; and to definitively disable the Gazan rocket system that could threaten unilateral Israeli development.”

To Israel’s bane, he said, “Palestinians are in the position to prevent Israel from developing that gas, and they cannot be stopped from deterring the development of that gas.” He was talking about platforms that Israel could build if it were to unilaterally take over the Gaza Marine field and extract its resources without the consent of the Palestinian government.

“Anybody that builds a platform out there – even those ridiculous improvised tiny little rockets that Hamas can build, even those will destroy that,” he said, adding:

They’ve achieved a 90 percent kill rate with those rockets, but a 90 percent kill rate is worthless. If they shoot a hundred rockets at those platforms, 10 of them are gonna get through, four of them are gonna land, and the platform’s gone. Nobody’s gonna develop it in that situation.”

GAZA’S HOPE

Mohammad Mustafa, the deputy prime minister and the national economy minister of the Palestinian government, disagrees with Schwartz’s assessment of the situation.

Speaking to MintPress from Palestine, Mustafa said: “I don’t think the war that took place [last summer] has any direct relations with gas, to be honest with you.” He says the conflicts are multifaceted, sometimes related to security, political progress (or lack thereof), and “sometimes commercial interests.”

Mustafa did say, however, that Israel was at one point interested in buying the gas for themselves, and that could have been a “complicating factor.”

The Financial Times reported in October 2013 that the Netanyahu government was “very supportive” of the Gaza Marine project. However, that position shifted radically between the end of 2013 and June 2014, when Israel launched Operation Protective Edge.

Mustafa says the possibility to develop these offshore reserves is not too far off in the future. He told MintPress: “In 1999 and 2000, BG [British Gas] and the consortium worked on checking the reserves and technical tests to ensure that the gas was available in commercially viable volumes, and that’s now proven.”

The consortium he spoke of comprises BG, Consolidated Contractors Company (CCC) and the Palestine Investment Fund (PIF), which has been given exclusive rights to explore the fields. Mustafa is also chairman of the Board of Directors of the PIF, a publically-owned investment company used to strengthen the local economy.

He explained: “Since then [1999 and 2000], the consortium has been trying very hard to develop the reserves, unfortunately without success.”

The Palestinian Authority faces two challenges: the political consent of Israel to develop the gas, and BG’s attempt to find credit-worthy buyers for the gas.

Yasser Arafat, who was president of the PA and leader of the Palestine Liberation Army when the gas was discovered in 1999, proclaimed: “It’s a gift from God to us, to our people, to our children,” adding, “This will provide a solid foundation for our economy, for establishing an independent state with holy Jerusalem as its capital.”

Indeed, the West Bank and Gaza, which depend on Israel for their energy needs, have long been reeling from energy-related issues that stymy the country’s growth. Gaza’s power plant was bombed by Israel last year, and the territory suffers from daily blackouts that can last more than 12 hours. The energy crisis affects everything from electricity to water, to medical supplies, to sewage treatment.

Development of the Gaza Marine offshore natural gas has the power to transform Palestine. A February policy paper from the Brookings Institution asserts that exploitation of the field would bring in $2.5 billion to $7 billion, help desalinate water, develop agriculture, become a major source of domestic electricity production, and help eliminate chronic debt.

ISRAEL’S CHALLENGES

However, Israel stands to benefit most from gas discoveries, not only because it is the dominant military force in the region, but also because some of the largest fields in the world have been discovered in Israeli territory.

But it won’t be able to do reap those benefits without first placating its own market regulators and currying favor with its gas-needy neighbors, which eschew Israel’s violence toward the Palestinians and Lebanese.

Israel’s gas fields are only partially developed because of regulatory opposition from the country’s antitrust commissioner, David Gilo, who recently resigned from his position due to a disagreement with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s office over regulation of the gas market.

In a statement to the press released on May 25, Gilo said:

My decision stems from a number of considerations, primarily from the news that the government, in particular the Prime Minister’s Office, the Finance Ministry and the Energy Ministry, will do all that they can to promote the outline formulated recently in the natural gas sector – an outline that I am convinced will not bring competition to this important sector.”

The outline he was referring to was a compromise agreement made between two shareholder companies in development of the country’s gas fields — Delek Group, an Israeli energy and infrastructure company, and Noble Energy, an American energy firm based out of Houston. The agreement stipulates that, among other provisions, Delek would end all of its operations in the Tamar field within six years, and Noble would reduce its shares from 36 percent to 25 percent.

However, decisions about how to move forward have not yet been made, and development of the Leviathan field remains stalled, both in terms of development and gas sales to neighbors.

Allison Good, an analyst who focuses on energy security and geopolitics in the Eastern Mediterranean and Eurasia, wrote in The National Interest last month:

The government has only approved one export agreement so far—the Tamar partnership’s letter of intent with Arab Potash Co. and Jordan Bromine Co. to export 1.87 billion cubic feet of gas over fifteen years. No other major export deals have been authorized. The Leviathan partnership has signed letters of intent to export gas to both the Jordanian Electric Power Company (JEPCO) and BG Group’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) facility in Egypt, while the Tamar partnership has signed a letter of intent with Union Fenosa Gas to supply the Spanish company’s LNG facility, also located in Egypt.”

She added: “Of course, none of these letters of intent have resulted in signed, binding contracts.”

Good advocated that Israel should expedite exporting licenses to the companies to show good faith, and to secure deals that may not be long in coming as Jordan and Egypt are not as dependent on Israeli gas as they were in the past. Both countries are currently being supplied by Qatar and Algeria.

OPPOSITION TO ISRAEL’S GAS

Further complicating Israel’s perceived good fortune in its gas finds is that the people in the countries Israel wishes to sell its gas to view Israel as an enemy.

Dozens of Jordanians gathered in front of Jordan’s House of Representatives on May 26 to protest the country’s agreement to buy gas from Israel.

Every time they [Jordanians] turn the lights on in their homes and offices, every time they charge their phones and laptops, they will be paying for the atrocious acts Israel regularly commits against the Palestinians.”

The deal would see Jordan pay $15 billion over 15 years, $8.4 billion of which would go directly to the Israeli government, potentially funding future wars against Palestinians, who currently comprise approximately half of Jordan’s 6.5 million people.

Samar Saeed, a Jordan-based journalist, says the gas deal is bad for Jordan — and Jordanians know it. She wrote in Muftah, a publication that focuses analysis on the Middle East and North Africa: “Every time they [Jordanians] turn the lights on in their homes and offices, every time they charge their phones and laptops, they will be paying for the atrocious acts Israel regularly commits against the Palestinians.”

[S]hould the agreement be signed, it would kill the spirit of resistance and solidarity that Jordanians have always demonstrated against Israel’s military occupation of Palestine, including through various boycott movements that relentlessly advocate against government efforts to normalize relations between Jordan and Israel.”

LEBANON

Excitement over the prospect of potential gas discoveries has gripped the Land of the Cedars as well.

Three gas companies — Total, Shell and Engie (previously GDF Suez) — along with two local Lebanese banks — Crédit Libanais and BBAC — sponsored an oil and gas forum on Monday in Beirut to discuss the development of the country’s oil and gas sector. Yet no oil or gas has been discovered in Lebanon to date.

The country’s civil society is ramping up efforts as well. The Lebanese Oil and Gas Initiative, a non-governmental organization based in Beirut that promotes the transparent and sound management of Lebanon’s oil and gas resources, claims it is developing “a network of Lebanese experts in the global energy industry” to “provide them with a platform to educate Lebanese policy makers as well as Lebanese citizens on the key decisions facing the oil and gas industry.”

Hype surrounding the sector hit a fever pitch in 2010, when it was thought that the Leviathan and Tamar gas fields extended into Lebanese territory. Some of the first militarized rhetoric concerning the offshore finds came from Israel at the time.

“We will not hesitate to use our force and strength to protect not only the rule of law but the international maritime law,” said Uzi Landau, Israel’s national infrastructure minister, in 2010 upon hearing that the speaker of Lebanon’s parliament claimed the gas fields extended into Lebanese territory.

However, the Lebanese government later conceded to the United Nations that the fields are not located in Lebanon’s territorial waters.

With U.S. Geological Survey estimates that 122 trillion cubic feet of gas lie under the Levantine Basin, government, civil society and investors still have no doubt that these reserves extend into their own territory.

Indeed, Madeleine Moreau, a Beirut-based security and conflict resolution analyst, recently wrote in Global Risks Insight, a website which provides expert political risk analysis for businesses and investors: “Initial 3-D seismic surveys off the coast of Lebanon suggest a high probability that there are vast natural fields of oil and gas supplies. These resources could gross over $100 billion in revenues over the next 20 years for the country.”

The biggest challenge for Lebanon remains a political one, as the country has not been able to elect a president for almost two years. The upcoming oil and gas forum will focus specifically on the issue of governance.

The country has been encouraged to quickly resolve its differences, build a government, and develop the gas sector to benefit from the potential economic windfall, which could help with crushing debt and other developmental problems. But Lebanon is also being encouraged to develop the sector so the country can become an important player in the energy market, which would spur world powers to invest in its stability.

Michael Schwartz, the sociology professor and author, remarked that it is ironic the region is facing so many geopolitical threats at the same time demand for gas has gone up, because the constant government stalling is preventing the resources from being extracted.

“It’s ultimately saving the environment,” he said, laughing.