After President Biden formally announced his plan to withdraw from Afghanistan by September 11th, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki was asked if special operations soldiers would remain in the country under the plan, which she declined to answer.

“I’m obviously not going to get into operational specifics from the podium,” Psaki said when asked if the removal of combat troops by September 11th will include withdrawing Special Forces.

“I will say that we may — we will have what is needed to secure a diplomatic presence,” Psaki added. “And those assessments will be made over the coming months and obviously led by the Defense Department and State Department in coordination.”

The US officially has 2,500 troops in Afghanistan currently, although reports have said the number is closer to 3,500. Besides soldiers, the US also has thousands of contractors working for the US military in the country. According to numbers released in January, there are over 18,000 Pentagon contractors in Afghanistan.

When Biden’s plan was first reported on Tuesday, current and former US officials told The New York Times that some sort of US presence will continue in Afghanistan.

The Times report reads:

“Instead of declared troops in Afghanistan, the United States will most likely rely on a shadowy combination of clandestine Special Operations forces, Pentagon contractors and covert intelligence operatives to find and attack the most dangerous Qaeda or Islamic State threats, current and former American officials said.”

When announcing his withdrawal plan, President Biden said the US needed to reshuffle its resources to better confront China, which is now a priority of the Pentagon. Considering Afghanistan’s Central Asian location and the fact that it shares a small border with China’s Xinjiang province, the US will undoubtedly at least maintain a CIA presence in the country.

Mercenaries R Us

The meaninglessness of President Biden’s announcement becomes apparent when we consider that the Pentagon employs more than seven contractors for every serviceman or woman in Afghanistan, an increase from one contractor for every serviceman or woman a decade ago.

As of January, more than 18,000 contractors remained in Afghanistan, according to a Defense Department report, when official troop totals had been reduced to 2,500.

These totals reflect the U.S. government’s strategy of outsourcing war to the benefit of private mercenary corporations, and as a means of distancing the war from the public and averting dissent, since relatively few Americans are directly impacted by it.

Most of the mercenaries are ex-military veterans, though a percentage are third-country nationals who are paid meager wages to perform menial duties for the military.

One of the biggest mercenary companies is DynCorp International of Falls Church Virginia, which as of 2019 had received over $7 billion in government contracts to train the Afghan army and manage military bases in Afghanistan.

From 2002 to 2013, DynCorp received 69 percent of all State Department funding. Forbes Magazine called it “one of the big winners of the Iraq and Afghan Wars” — the losers being almost everyone else.

A blueprint for U.S. strategy in Afghanistan is the 1959-1975 secret war in Laos, where the CIA worked with hundreds of civilian contractors who flew spotter aircraft, ran ground bases, and operated radar stations in civilian clothes while raising its own private army among the Hmong to fight the pro-communist Pathet Lao.

The CIA and Special Forces have again attempted to recruit tribal elements in Afghanistan and, like in Laos, have become enmeshed in inter-tribal and sectarian feuds.

For years, U.S. Special Forces operatives have also been training Afghan security forces as a proxy army and running Phoenix-style snatch and grab and assassination missions, which are poised to continue — despite the formal troop withdrawal.

What Uncle Sam really wants in Afghanistan

Republican hawk Jim Inhofe lambasted Biden’s withdrawal plan, stating that this was a “reckless and dangerous decision. Arbitrary deadlines would likely put our troops in danger, jeopardize all the progress we’ve made, and lead to civil war in Afghanistan — and create a breeding ground for international terrorists.”

Inhofe it should be noted is a war profiteer. He invested in the stocks of leading arms manufacturer Raytheon at the same time he was calling for an increase in the defense budget as Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee.

Inhofe’s assessment is flawed because, among other reasons, the U.S. has not made much progress in 19 years of war (the Taliban, according to the Council on Foreign Relations, is stronger than at any point since 2001 and controls about one-fifth of Afghanistan), and Afghanistan was never really a breeding ground for international terrorists.

The 9/11 hijackers mostly came from Saudi Arabia, and the Taliban agreed to turn over Osama Bin Laden to an international court after the 9/11 attacks, which they never supported.

The Afghan War will go on indefinitely not because of the threat of terrorism — which is accentuated by the U.S. military presence — but because the United States will not concede ground in the region.

The U.S. has announced intentions to retain at least two military bases in Afghanistan after the official troop drawdown, and set up over 1000 bases during the war.

Uncle Sam also covets Afghans mineral wealth. A 2007 United States Geological Service survey discovered nearly $1 trillion in mineral deposits, including huge veins of iron, copper, cobalt, gold, and critical industrial metals like lithium, which is used in the manufacture of batteries for laptops and blackberries.

An internal Pentagon memo stated that Afghanistan could become the “Saudi Arabia of lithium.”

In 2001, when the U.S. first invaded Afghanistan, it was in the process of expanding its military infrastructure in Central Asia. Afghanistan provided a key way-station to this new “oil dorado,” which holds as much as 200 billion barrels of oil — about 10 times the amount found in the North Sea, and a third of the Persian Gulf’s total reserves.

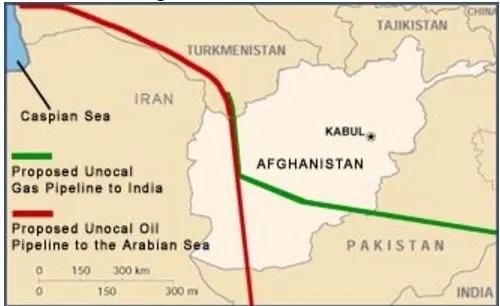

Afghanistan was further valued at the time as a key location for an oil pipeline that would transport Central Asian oil to the Indian Ocean while bypassing Russia.

In the 1990s, the Southern California oil company Unocal began taking steps to build the pipeline, even courting the Taliban. In 2018, ground was broken on a new pipeline project backed by the United States that will carry oil from Turkmenistan to northern India.

The U.S. ruling establishment’s greatest fear is that a complete U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan might result in the U.S. losing a strategic foothold to its main geopolitical rivals, China and Russia, in Afghanistan.