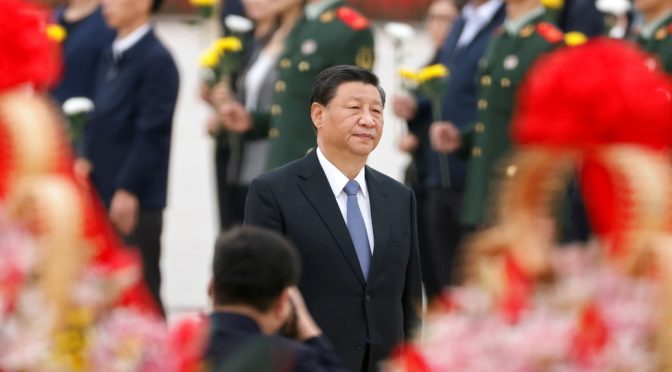

Now anointed with the same status afforded to Mao and Deng, Xi has the opportunity to usher in a new era that will complete his vision for the rejuvenation of China while dealing with the threat posed by America.

The country’s ruling Communist Party (CPC) passed a significant resolution on Thursday, affirming the 68-year-old leader as a key figure in the party’s history, elevating him to the same historical status as Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping.

The document, a summary of the party’s history, addresses its key achievements and future directions. It’s only the third of its kind since the party was founded 100 years ago – the first was passed by Mao in 1945 and the second by Deng in 1981.

This consolidates Xi’s legacy, ideology and policies as a historic epoch for the party and country’s direction. Inevitably, the Western mainstream media interpreted it critically, claiming Xi was centralizing power, building a personality cult, and taking China in the wrong direction at a time of growing geopolitical friction.

But what does this affirmation of the man really mean? Why is it happening? And how can we better understand these events other than through the caricature of stereotypical villainy, which portrays Xi as someone who is taking the country backwards, or as a threat to the world?

In the century of its existence, the CPC has shown itself to be an adaptive institution which has used pragmatism to respond to various crises, catastrophes and, for that matter, its own mistakes. It has also employed resilience to succeed against the odds, constantly re-evaluating itself. From the Long March, when its members retreated thousands of miles to escape persecution; to fighting guerrilla warfare against the Japanese; to conquering all of China and building a revolutionary state through both successes and failures; the party has utilized this accumulated wisdom and experience to adapt and sustain power in a constantly changing world. Its mission has been to re-establish China as a modern, sovereign and powerful nation, reversing its “century of humiliation.”

Xi Jinping is a living example of such constant re-evaluation, or the “scientific method” that the party utilizes, not just through what he does but how he links together this whole history. He is, after all, the first leader of the country who has spent all his life under nothing but the People’s Republic of China, seeing it all from the beginning to the present day. His childhood was the Mao era, when his dad was a senior party official who was later purged and imprisoned, and witnessed first-hand the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution,

At 15, Xi was sent to the countryside for “re-education” and hard labor for seven years – an experience that has figured large in his official story. Far from rebelling against the party, Xi embraced it. He tried to join it several times, and when he was finally accepted in 1974, he worked hard to rise up the ranks, a journey that resulted in him being picked as president in 2012.

Now facing off against the US, Xi is leading China into an era of his own, pinning together the fluidity of the party’s existence. It is this shifting situation today, as well as his own interest in socialist theory, that are defining his tenure. Before him, it was widely assumed the party was on an inevitable trajectory of reform and liberalization which would eventually change China to mirror the West, the so-called “end of history” thesis which placed faith in liberalism’s inevitable and logical victory. It is no surprise that in Western eyes, Xi Jinping is erroneously depicted as the man who is taking the country backwards.

But that doesn’t help us understand what he is doing, or why he is doing it. China has changed because its place in the world has changed, as has what the party perceives is necessary for its national progress. The hopes and optimism of the Deng Xiaoping era never took notice of the reality that, in the 1980s, China was a weak and poor country contingent upon Western goodwill for its progress and development in moving past the mistakes of the Mao era. Not because it was on a path to one day dismantling communism, as liberals assumed, or had already disregarded it in all but name, and not because its goals were different. A phrase commonly associated with the Deng period was that China was “keeping a low profile,” and in many respects it was.

But what Xi now sets out for the future is a testament to the reality that such a world no longer exists, and is no longer suitable for what China needs. It is impossible for it to “keep a low profile” today – the country has grown to become the world’s second-largest economy, and is at a critical economic juncture whereby it must take the leap from becoming a per capita middle-income country towards being a high one. In line with that, it faces considerable challenges from a US, finally awakened from the fantasy that Beijing was going to morph into its own image, which no longer tolerates a rising China.

Such new realities required a structural overhaul of how China is governed. The China of the past may have coincided with and complemented US interests, both economic and strategic, but no longer is that the case. The West believed it always knew what was good for China, but the time has come whereby what is in China’s interests may conflict with the West’s agenda.

As a result, this “new era” of Xi Jinping is not as much about the man himself as it is about these new circumstances and needs, even if he is at the center of it. Would the more “loose and open approach” of previous administrations under Deng, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao have been suitable for these new challenges? Where the party role is downplayed and where businesses hold enormous sway? Could that system deal with attempts by the US to block China’s rise in strategic technologies or assert its national sovereignty across several areas? Administrations that ignored wealth inequality and pretended China was a socialist country in name only?

It is only natural that, in an environment of growing insecurity and uncertainty and with more specific and tailored goals, the state pragmatically adapted to reassert itself. Americans like to frequently blame Xi for the decline in relations between the two countries, but it is foolish to think the US could have accepted a rising communist China under any circumstance, or that goodwill from Beijing could have kept them at bay.

These reasons are why Xi has been more than willing to take considered risks preemptively, such as responding to American military encirclement by advancing China’s claims in the South China Sea, to build the Belt and Road to offset strategic economic vulnerabilities, or to bring the hammer down on Hong Kong and other regions before they became liabilities.

They may have all served to exacerbate the emerging cold war, yet they were one step ahead of what Xi perceived was inevitably coming: the increasing US moves to contain and suppress China, which are here now. The China of his predecessors was not prepared to meet that challenge. It is now.

Yet there is more to it. Xi’s decisions mirror the reality that China can no longer go with development for the sake of development, or growth for the sake of growth, because the consequences of its boom create new problems and side-effects, which will not go away on their own. We see, for example, how the Evergrande situation – while not the spectacular disaster the Western mainstream media have made it out to be – nonetheless represents a shift away from real estate and debt-binging growth.

The live-and-let-be capitalism of the West is not the solution for China. One wonders what would have happened if the Evergrande situation were allowed to continue in the fashion it has. China’s clampdowns on Big Tech also look at the long-term, bigger picture. It is easy to write everything off as a mere act of control or dominance concerning the party, but it requires real critical thinking to recognize what is driving these changes and why the Xi era is changing China’s direction for a new epoch.

We should understand China’s own interpretation of its party history like this: Mao established a revolutionary state, albeit one which did not function well bureaucratically or economically. Deng then took that legacy and refined it, creating a state which functioned and thrived under the process of reform and opening up, utilizing geopolitical realism to court the West. Now, Xi Jinping, with a modern China facing resistance from the West as an emerging power, is reasserting the authority and leadership of the party to adapt the country not only for its growth needs, but to continue moving forwards in what he describes as “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

The party has always acted to ensure its survival, but that survival is inseparably tailored to the success of the broader goal of the revival of China. To reduce the CPC to a cliche of a small, evil little group of men obsessed with power and on a mission of global conspiracy is both ignorant, unhelpful and completely off the mark. China has, whether you agree with it or not, moved into a new phase of its history in response to its new needs and circumstances. In doing so, Xi has cemented himself as ruler for life and placed himself on the same level as Mao.

Tom Fowdy is a British writer and analyst of politics and international relations with a primary focus on East Asia.