Given the breadth and depth of deprivation in the richest country in the world, it should be surprising how little attention has been paid to the priorities of poor and low-income voters in the 2022 election season, writes Liz Theoharis.

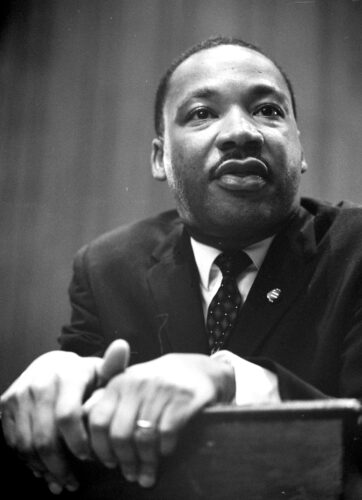

Ours is an ever more unequal world, even if that subject is ever less attended to in the United States. In his final book, Where Do We Go From Here?, Reverend Martin Luther King wrote tellingly,

“The prescription for the cure rests with the accurate diagnosis of the disease. A people who began a national life inspired by a vision of a society of brotherhood can redeem itself. But redemption can come only through a humble acknowledgment of guilt and an honest knowledge of self.”

Neither exists in this country. Rather than an honest sense of self-awareness when it comes to poverty in the United States, policymakers in Washington and so many states continue to legislate as if inequality weren’t an emergency for tens, if not hundreds, of millions of us. When it comes to accurately diagnosing what ails America, let alone prescribing a cure, those with the power and resources to lift the load of poverty have fallen desperately short of the mark.

With the midterm elections almost upon us, issues like raising the minimum wage, expanding healthcare, and extending the Child Tax Credit (CTC) and Earned Income Tax Credit should be front and center.

Instead, as the U.S. faces continued inflation, the likelihood of a global economic recession and the possibility that Trumpists could seize control of one or both houses of Congress (and the legislatures of a number of states), few candidates bother to talk about poverty, food insecurity or low wages. If anything, “poor” has become a four-letter word in today’s politics, following decades of trickle-down economics, neoliberalism, stagnant wages, tax cuts for the rich, and rising household debt.

The irony of this “attentional violence” towards the poor is that it happens despite the fact that one-third of the American electorate is poor or low-income. (In certain key places and races raise that figure to 40 percent or more.)

After all, in 2020, there were over 85 million poor and low-income people eligible to vote. More than 50 million potential voters in this low-income electorate cast a ballot in the last presidential election, nearly a third of the votes cast.

And they accounted for even higher percentages in key battleground states like Arizona, Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Texas and Wisconsin, where they turned out in significant numbers to cast ballots for living wages, debt relief and an economic stimulus.

To address the problems of our surprisingly impoverished democracy, policymakers would have to take seriously the realities of those tens of millions of poor and low-income people, while protecting and expanding voting rights.

After all, before the pandemic hit, there were 140 million of them: 65 percent of Latinx people (37.4 million), 60 percent of Black people (25.9 million), 41 percent of Asians (7.6 million), and 39.9 percent of white people (67 million) in the United States. Forty-five percent of our women and girls (73.5 million) experience poverty, 52 percent of our children (39 million), and 42 percent of our elders (20.8 million). In other words, poverty hurts people of all races, ages, genders, religions, and political parties.

Poverty on the Decline?

Given the breadth and depth of deprivation, it should be surprising how little attention was paid to the priorities of poor and low-income voters in the 2022 election season. Instead, some politicians are blaming inflation and the increasingly precarious economic position of so many on the modestly increasing paychecks of low-wage workers and pandemic economic stimulus/emergency programs.

That narrative, of course, is wrong and obscures the dramatic effects in these years of Covid supply-chain disruptions, the war in Ukraine and the price gouging of huge corporations extracting record profits from the poor. The few times poverty has hit the news this midterm election season, the headlines have suggested that it’s on the decline, not a significant concern to be urgently addressed by policy initiatives that will be on some ballots this November.

Case in point, in September, the Census Bureau released a report concluding that poverty nationwide had significantly decreased in 2021. Such lower numbers were attributed to an increase in government assistance during the pandemic, especially the enhanced Child Tax Credit implemented in the spring of 2021. No matter that there’s now proof positive such programs help lift the load of poverty, too few political candidates are campaigning to extend them this election season.

Similarly, in September, the Biden administration convened the White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health, hailed as the first of its kind in more than half a century. But while that gathering may have been an historic step forward, the policy solutions it backed were largely cut from the usual mold — with calls for increases in the funding of food programs, nutritional education and further research.

Missing was an analysis of why poverty and widening inequality exist in the first place and how those realities shape our food system and so much else. Instead, the issue of hunger remained siloed off from a wider investigation of our economy and the ways it’s currently producing massive economic despair, including hunger.

To be sure, we should celebrate the fact that, because of proactive public intervention, millions of people over the last year were lifted above income brackets that would, according to the Census Bureau, qualify them as poor.

But in the spirit of Reverend King’s message about diagnosing social problems and prescribing solutions, if we were to look at the formulas for the most commonly accepted measurements of poverty, it quickly becomes apparent that they’re based on a startling underassessment of what people actual need to survive, no less lead decent lives. Indeed, a sea of people are living paycheck-to-paycheck and crisis-to-crisis, bobbing above and below the poverty line as we conventionally know it.

By underestimating poverty from the start, we risk reading the 2021 Census report as a confirmation that it’s no longer a pressing issue and that the actions already taken by government are enough, rather than a baseline from which to build.

Last month, for example, although a report from the Department of Agriculture found that 90 percent of households were food secure in 2021, at least 53 million Americans still relied on food banks or community programs to keep themselves half-decently fed, a shocking number in a country as wealthy as the U.S. More than 20 percent of adults in the last 30 days have reported experiencing some form of food insecurity.

In other words, we’re talking about a deep structural problem for which policymakers should make a commitment to the priorities of the poor.

An Accurate Diagnosis

If the political history of poverty had been recorded on the Richter scale, one decision in 1969 would have registered with earthshaking magnitude. That Aug. 29, the Bureau of the Budget delivered a dry, unfussy memo to every federal government agency instructing them to use a new formula for measuring poverty. This resulted in the creation of the first, and only, official poverty measure, or OPM, which has remained in place to this day with only a little tinkering here and there.

The seeds of that 1969 memo had been planted six years earlier when Mollie Orshansky, a statistician at the Social Security Administration, published a study on possible ways to measure poverty.

Her math was fairly simple. To start with, she reached back to a 1955 Department of Agriculture (USDA) survey that found families generally spent about one-third of their income on food. Then, using a “low-cost” food plan from the Department of Agriculture, she estimated how much a low-income family of four would have to spend to meet its basic food needs and multiplied that number by three to arrive at $3,165 as a possible threshold income for those considered “poor.” It’s a formula that, with a few small changes, has been officially in use ever since.

Fast forward five decades, factor in the rate of inflation, and the official poverty threshold in 2021 was $12,880 per year for one person and $26,500 for a family of four — meaning that about 42 million Americans were considered below the official poverty line.

From the beginning though, the OPM was grounded in a somewhat arbitrary and superficial understanding of human need. Orshansky’s formula may have appeared elegant in its simplicity, but by focusing primarily on access to food, it didn’t fully take into account other critical expenses like healthcare, housing, childcare and education. As even Orshansky later admitted, it was also based on an austere assessment of how much was enough to meet a person’s needs.

As a result, the OPM fails to accurately capture how much of our population will move into and out of official poverty in their lifetimes. By studying OPM trends over the years, however, you can gain a wider view of just how chronically precarious so many of our lives are.

And yet, look behind those numbers, and there are some big questions remaining about how we define poverty, which say much about who and what we value as a society. For the tools we use to measure quality of life are never truly objective or apolitical. In the end, they always turn out to be as much moral as statistical.

What level of human deprivation is acceptable to us? What resources does a person need to be well? These are questions that any society should ask itself.

Since 1969, much has changed, even if the OPM has remained untouched. The food prices it’s based on have skyrocketed beyond the rate of inflation, along with a whole host of other expenses like housing, prescription medicine, college tuition, gas, utilities, childcare, and more modern but increasingly essential costs, including Internet access and cell phones.

Meanwhile, wage growth has essentially stagnated over the last four decades, even as productivity has continued to grow, meaning that today’s workers are making comparatively less than their parents’ generation even as they produce more for the economy.

Billionaires, on the other hand… well, don’t get me started!

The result of all of this? The official poverty measure fails to show us the ways in which a staggeringly large group of Americans are moving in and out of crisis during their lifetimes. After all, right above the 40 million Americans who officially live in poverty, there are at least 95-100 million who live in a state of chronic economic precarity, just one pay cut, health crisis, extreme storm, or eviction notice from falling below that poverty line.

The Census Bureau has, in fact, recognized the limitations of the OPM and, since 2011, has also been using a second yardstick, the Supplemental Poverty Measure(SPM). As my colleague and poverty-policy expert Shailly Gupta-Barnes writes, while factoring in updated out-of-pocket expenses the “SPM accounts for family income after taxes and transfers, and as such, it shows the antipoverty effects of some of the largest federal support programs.”

This is the measure that the Census Bureau and others have recently used to show that poverty is dropping and there’s no doubt that it’s an improvement over the OPM. But even the SPM is worryingly low based on today’s economy — $31,000 for a family of four in 2021. Indeed, research by the Poor People’s Campaign (which I co-chair with Bishop William Barber II) and the Institute for Policy Studies has shown that only when we increase the SPM by 200 percentage do we begin to see a more accurate picture of what a stable life truly beyond the grueling reach of poverty might look like.

Volcker Shock 2.0?

Taking to heart Reverend King’s admonition about accurately assessing and acknowledging our problems, it’s important to highlight how the math behind the relatively good news on poverty from the 2021 census data relied on a temporary boost from the enhanced Child Tax Credit.

Now that Congress has allowed the CTC and its life-saving payments to expire, expect the official 2022 poverty figures to rise. In fact, that decision is likely to prove especially dire, since the federal minimum wage is now at its lowest point in 66 years and the threat of recession is growing by the day.

Indeed, instead of building on the successes of pandemic-era antipoverty policies and so helping millions (a position that undoubtedly would still prove popular in the midterm elections), policymakers have acted in ways guaranteed to hit millions of people directly in their pocketbooks.

In response to inflation, the Federal Reserve, for instance, has been pursuing aggressive interest rate hikes, whose main effect is to lower wages and therefore the purchasing power of lower and middle-income people. That decision should bring grimly to mind the austerity policies promoted by economist Paul Volcker in 1980 and the Volcker Shock that went with them.

It’s a cruel and dangerous path to take. A recent United Nations report suggests as much, warning that inflation-fighting policies like raising interest rates in the U.S. and other rich countries represent an “imprudent gamble” that threatens “worse damage than the financial crisis of 2008 and the Covid-19 shock in 2020.”

If the U.S. is to redeem itself with a vision of justice, it’s time for a deep and humble acknowledgment of the breadth and depth of poverty in the richest country in human history. Indeed, the only shock we need is one that would awaken our imaginations to the possibility of a world in which poverty no longer exists.