Orthodox economics is the ideology of the rich and powerful, writes Dian Maria Blandina. Poor countries such as Sudan, that are trying to develop, cannot afford a regime of free trade.

Sudan is experiencing its fourth week of conflict between two military factions, which has caused the death of over 700 people.

Sudanese civilians have fled the capital and the country altogether while the fighting continues with no end in sight. Commentators have so far focused on the military factions and ethnic conflicts.

A reductive explanation has been given for the food crisis in Sudan, such as economic crisis, climate change and the Ukraine war. The significance of macroeconomic policies and the institutions that promote them at the root of these crises tend to be overlooked.

Toppling Over the Breadbasket

The IMF imposed liberalization in Sudan, particularly in the agricultural sector, to promote exports. Liberalization means removing any barriers to trade and eliminating obstacles to foreign investment, while at the same time reducing the size and power of the government to regulate the economy.

Orthodox economics is the ideology of the rich and powerful. Poor countries trying to develop like Sudan cannot afford a regime of free trade. Sudan should have been left to develop its agricultural sector to serve its own people first.

Seeing Sudan in the news now, it’s hard to imagine that it was once destined to be the “breadbasket of Africa.” Sudan is not only rich in oil and minerals, but also arable land.

As explained in Oxfam’s 2002 report, rapid agricultural liberalization was a key cause of rising poverty and food insecurity in Africa. The consequences are still experienced to this day.

Liberalization policies are also eerily similar to extractive practices in the colonial era; in this case, turning Sudan into the world’s farm while the people starve. Back then, there were also local and not-so-local businesses and politicians who facilitated the colonial powers in extracting Africa’s riches and exploiting its labor force.

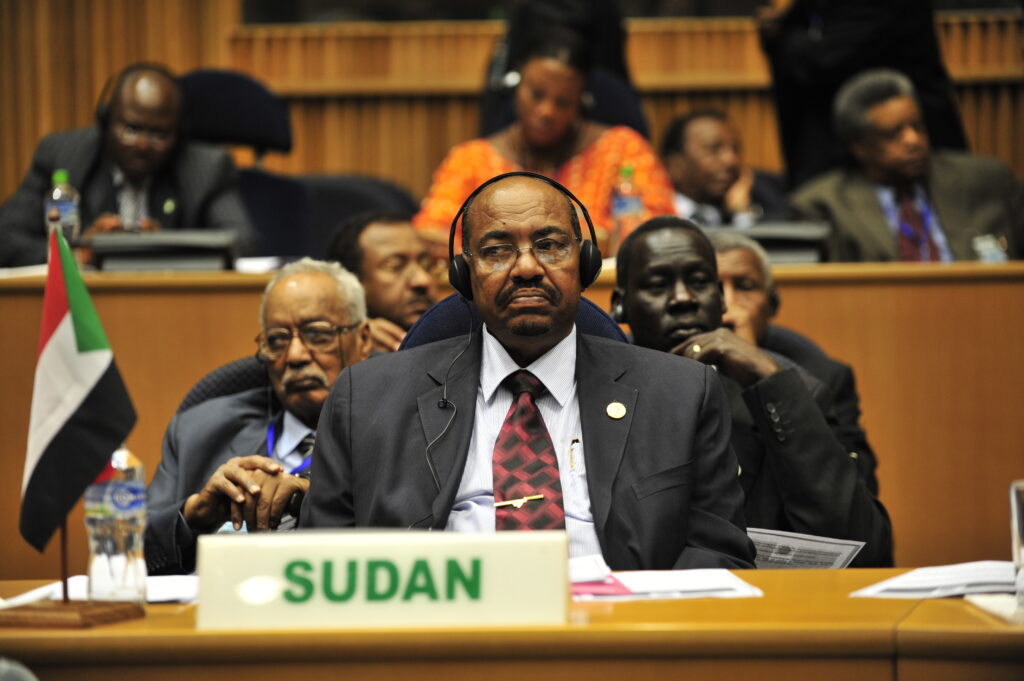

Sudan has a diverse population of over 600 ethnic groups speaking 400 languages, with Islam being the predominant religion. The country has experienced two civil wars, three coup d’états and a 30-year military dictatorship under Omar Al-Bashir that ended in 2019 following an uprising.

A transitional government was established under Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok, but it was fragile, and in October 2021, the military dissolved the government and placed the prime minister under house arrest, leading to protests and violent crackdowns that have resulted in more than 100 civilian deaths and many more injuries.

The IMF has long been involved with Sudan. To date, Sudan has undergone at least 11 IMF programs in between civil wars and conflicts. Between 1979 and 1985 alone, under Nimeiri’s regime, there were five IMF loan programs in Sudan. Outside of the programs, the IMF maintained counsel to the government, giving policy advice that would “help” Sudan’s creditworthiness and access to the international market.

From the start of their relationship, Sudan has been in the weaker position. Highly ambitious development projects in the 1970s combined with years of ill-advised investments left the country in a severe deficit and with no bargaining power against international institutions and foreign powers.

The IMF dealt with Sudan in a very autocratic manner, handing down conditionalities and expecting the Sudanese government to implement them with no care of how it’s done.

An unusual feature of the IMF-Sudan relationship was that Sudan was almost always expected to conceive and implement austerity on its own, prior to receiving loans.

The IMF also dealt with Sudan harshly, cutting off credits and aid at the slightest sign of non-compliance or policy disagreement, and imposing increasingly severe terms. The dynamic was so perplexing that scholars used Sudan as a case study to understand power struggle in IMF programs.

Protests, Riots, Coup, Repeat

IMF “riots” took place many times in Sudan throughout the 1970s and ’80s because of cuts in subsidies and currency devaluation which made basic commodities expensive.

For a large and diverse country divided by factions like Sudan, such policies quickly turned to social unrest. One of these protests in 1985 led to a coup d’etat when the military intervened.

Scholars have studied social unrest during IMF programs over the past 40 years and found a correlation with coup d’états. IMF programs create winners and losers among both common people and regime elites, leading the “losing” elites to put up a new leader who is more likely to reject conditionalities unfavorable to their interests.

Sudan’s diverse nature and complex historical context have contributed to internal conflicts in the country. The IMF’s push for foreign investments has brought in foreign actors with their own interests, further complicating matters and making Sudan a hotbed for geopolitical struggles and power plays.

In 2012, anti-austerity protests brought thousands of people to the streets of the capital, Khartoum. Citizens were angry over the fuel-subsidy cuts imposed by the IMF combined with rising inflation and called for Bashir to leave the presidency.

Clashes ensued. It also led to another coup d’etat attempt which ultimately failed.

Still, the IMF pushed for subsidy cuts demanding the government “communicate the shortcomings of price subsidies and the urgency of the need for reform.”

It noted that cuts should be implemented gradually, while also acknowledging that “given the unstable political conditions, [subsidy reform] should be launched ahead of any further price increase.”

Subsidies may just be a numbers game to the IMF, but for the people, it is a social contract that lets them know that the government takes care of their well being, especially in times of crisis. Protests continued into 2013 and a violent crackdown ensued with a death toll up to 230.

The present conflict in Sudan has its roots in December 2018, when then President Omar al-Bashir ended subsidies on fuel and wheat, again, in accordance with the IMF’s recommendations.

This time the coup against Bashir was successful. But the protests and violent crackdowns that continued until after the military took over once again cost hundreds of lives before finally a compromise was reached and a transitional government was formed.

Given this track record, it was a surprise when the civilian Prime Minister Hamdok entered into another IMF program in 2021 when it was supposed to be turning over a new leaf. Subsidy cuts began in 2020 prior to the signing of the agreement while the country was battling the Covid -19 pandemic and facing other challenges.

Since October 2021, the Sudanese people have protested the military takeover at the cost of hundreds of lives. On the surface, the “international community” seemed to punish the military coup by suspending aid and debt relief, but on the ground, the military regime was given a seat at the negotiating table, and perhaps even a position of priority in dictating the “peace terms.”

On the other hand, the demand from the people had been clear all along that they wanted justice, an end to the military regime and most importantly, a complete restructuring of Sudan’s economy so that the needs of the people could be served.

A real transformative process can only begin with first understanding the root causes of the people’s discontent, for example, by acknowledging that the military elites not only brutalize any form of dissent but also control the majority of Sudan’s natural resources which they use for themselves and foreign actors.

It is crucial to ensure that civil society organizations are given a priority seat at the negotiating table so that the voices of the common people can be heard and taken into account.